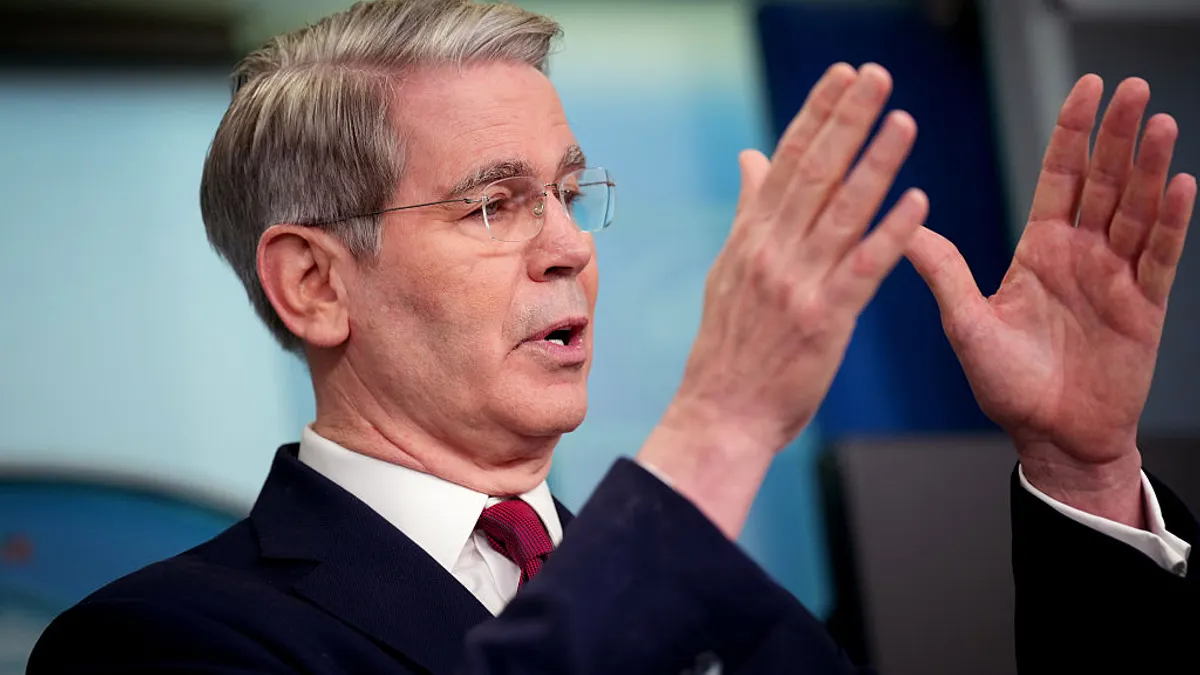

If your metrics are anywhere near good, now is the time to be out in the market raising money, Jeff Epstein, CFO emeritus at Bessemer Venture Partners and former finance leader at Oracle, Nielsen, and DoubleClick, said this week in a CFO Thought Leader podcast.

"The capital markets are open sometimes, they're closed sometimes, and it's really important to raise money when they're open," said Epstein. "Like today. My advice is, if you can raise money today, raise it now. The stock market's at an all-time high in spite of COVID and investors are eager to invest and interest rates are low."

To attract investors, Epstein said, CFOs must be able to tell the story of their company in numbers.

At Bessemer, the company looks for startups that have a chance of growing into companies worth $1 billion in six or seven years and have a playbook for getting there.

"If I'm the investor, I'd like to have metrics that give proof we’ve already figured out the playbook," he said.

The proof points he looks for start with product-market fit and a repeatable sales process. "Do I have a high net promoter score?" he said. "Are a high percentage of our customers referenceable, where the [prospect] can just randomly call any customer and they get an endorsement that the product is great? Are 75% of my sales people making quota?"

A second proof point is a two-year customer acquisition payback period. "If you take all of the customer acquisition costs — marketing and sales — and you say, 'How much gross profit per year do I bring in from my new customer, marketing and sales? Does that payback happen in a year, two years, three years?' At Bessemer, we want to see that payback in under two years," he said.

He also looks at the company's win rate — the percentage of deals the company wins compared to the percentage its competitors win. "When I lose, who do I lose to?" he said. "Why don't I win? Do I do all direct sales or do I sell through partners? What’s my partner strategy? If I’m doing marketing, how much marketing do I get from Google, Facebook, other channels?"

Lastly, he looks at retention. "Once I have a reasonable business, can I keep my customers?" he said. "What's my gross renewal rate? If I start with 100 customers, a year later do I have 95 or 75? And the customers who are left, do they buy the same amount or less or more?"

The company doesn't necessarily need to have more customers at the end of the year, but it must be making more money on the customers it has.

"Maybe I start with 100 customers and I end up with 90, but the 90 who are left buy more, so I end up with $110 in revenue from the $100 in revenue before," he said. "So, I'm growing 10%, with no new customers."

If you have metrics that aren't as positive as you'd like, CFOs should not try to hide them when talking with investors; instead, show a plan for addressing them.

"Let's say 40% of my sales team make quota instead of 75%," he said. "Don't hide it. I tell investors, 'We have 40% of our sales team making quota; here's what we’re doing about it. We just hired a head of sales training.' Or, 'Our sales to the $10,000-customers are great while our sales to the $100,000-customers are poor. We just hired two new salespeople there.'"

Nasdaq crash

Raising money at the right time can come across as counter-intuitive sometimes, Epstein said.

In 2001, when he was CFO of DoubleClick, the early-internet advertising broker, the company had grown from $250 million to $13 billion in fewer than three years. Even though it was growing fast and generating a comfortable $500 million in annual revenue, it was a good market for raising money and so the executive team prepared for a $700 million capital raise.

"The famous saying is, raise money when you can, not when you need it," he said.

The day before they were to price the offering, though, USA Today published an article suggesting the company was lax on protecting people's privacy, fueling a sell-off of the company's stock.

"I was at an investor lunch where I was giving my presentation and I got a note saying I should call my office," said Epstein. "I call my office and they say to call Nasdaq, so I call Nasdaq and they say we've had a lot of sell interest in your stock. I asked what's going on, and they said, 'Did you read that article in USA Today this morning?'"

Epstein said he had, in fact, read the article but didn’t think anything of it because he felt the piece inaccurately portrayed the company's approach to privacy.

"Evidently, investors didn't agree, and Nasdaq said we have so much sell interest, we've stopped trading in your stock," he said.

After a huddle, the executives agreed to proceed with the offering, even though the stock was predicted to open the next day at a 20% drop in value.

"I argued strongly we should go ahead with the offering, because even at a $9 billion market value, we had $500 million in revenue," he said. "We were losing money and that was still 18 times revenue. That was still a great valuation. The fact that we were trading for more yesterday didn't matter. The question is, is this a good valuation today? Other people said no; we shouldn't go ahead with it because we don't want to prove to people they can damage us through this inaccurate portrayal of us being anti-privacy."

The decision to proceed with the offering proved prescient. A short time after their offering, 9/11 happened, and Nasdaq crashed.

"The stock went down substantially, but it saved the company," he said. "Even though the company was losing money, for the next several years we had all that money in cash on our balance sheet."

Epstein credited his experience working at First Boston during the 1987 market crash with giving him the insight to argue for the capital raise despite the drop in stock price.

"I felt I had such personal experience in the volatility in the capital markets that it underscored for me this idea that the capital markets are open sometimes, they're closed sometimes, and it's really important to raise money when you can," he said.