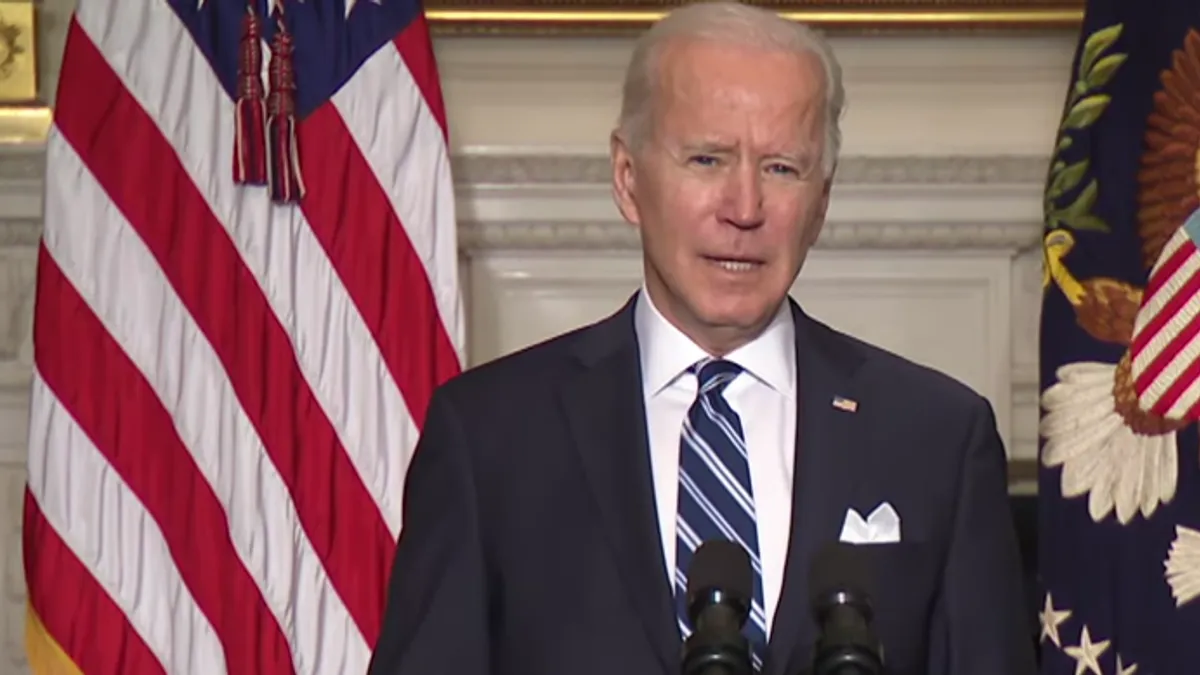

President Biden last week announced a sweeping plan to increase business competition in the United States, which he said has decreased in recent decades as big companies increasingly take commanding control over markets, but the plan faces hurdles that could limit how much impact it has.

Whether the government's main antitrust agency, the Federal Trade Commission, steps up its antitrust rulemaking or takes a more aggressive litigation approach, change will only come slowly, if at all, as companies in targeted industries fight back in a legal area that traditionally has been contentious and resistant to change.

"The administration wants to start the process of fundamentally changing how agencies approach markets," Andy Lacy, an attorney with the Goodwin law firm, told CFO Dive. "They recognize this will be a lengthy, drawn-out process. Their view is, you have to start somewhere."

Policy pushes

The executive order is built around 72 policy pushes that are intended to lower costs, raise wages, and make it easier for small businesses to compete against entrenched big players. The policy objectives lack teeth but could lead to new laws and rules down the road.

“Capitalism without competition isn’t capitalism,” Biden said in introducing the plan. “It’s exploitation.”

Probably most sweeping is a call for the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission to step up antitrust efforts, particularly in agriculture, healthcare and technology, in part through better coordination with other agencies and by taking a fresh look at past mergers to see if new challenges are appropriate.

To help these and the other competitiveness efforts, the administration is creating a White House Competition Council, led by the National Economic Council director.

“We’re now 40 years into the experiment of letting giant corporations accumulate more and more power,” Biden said. “What have we gotten from it? Less growth, weakened investment, fewer small businesses.”

Congressional focus

The antitrust effort is in line with a congressional antitrust push, which has focused on big technology companies like Facebook, Amazon and Google.

“Over the past 10 years, the largest tech platforms have acquired hundreds of companies — including alleged ‘killer acquisitions’ meant to shut down a potential competitive threat,” the White House said in a fact sheet. “Too often, federal agencies have not blocked, conditioned, or, in some cases, meaningfully examined these acquisitions.”

Last year a House antitrust subcommittee grilled Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Apple’s Tim Cook, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Google’s Sundar Pichai about anti-competitive practices, including the use of acquisitions to snuff out threats before they challenge their dominance.

The hearing looked especially close at Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram, the photo-sharing app, which Zuckerberg said in emails he was concerned could meaningfully hurt his company’s dominance in that area.

How much firepower the federal government could bring to a big antitrust case against Facebook is unclear, though. The FTC just last month lost an antitrust case against Facebook’s Instagram acquisition, with U.S. District Judge James Boasberg saying the agency failed to show Facebook is a monopoly.

“It is almost as if the agency expects the Court to simply nod to the conventional wisdom that Facebook is a monopolist,” Boasberg said in the decision.

The FTC has until the end of July to file an amended complaint.

The judge also dismissed another antitrust case against the acquisition. The judge said a group of state attorneys general waited too long to file their suit against Facebook for its acquisition of Instagram and also the WhatsApp messaging service. Those acquisitions happened in 2012 and 2014, respectively.

The FTC could take up that case. The judge said the FTC might have the authority to bring the same charges against the company as the attorneys general.

Long road

Whatever the FTC decides to do about Facebook, it and the government’s other antitrust agencies face a tough road acting on Biden's order, given the historical difficulty agencies have had showing companies are monopolies whose practices lead to higher consumer costs.

“As a practical matter, it is far from clear that the antitrust and other agencies will be able to deliver on the executive order’s goals,” said Lacy.

The two approaches the FTC could take — regulatory or litigation — both face hurdles. On the regulatory side, it's not clear the FTC has the authority to make rules in the antitrust area in the same way it does in the consumer protection area, so any rulemaking faces procedural challenges separate from any substantive challenges companies make. Just getting through the procedural challenges could take years, said Lacy.

In the courts, the FTC and the DOJ face steep hurdles because of the nature of antitrust cases, which tend to turn on abstract conceptual issues.

"You're litigating an entire industry — one company's conduct against another or a handful of companies," said Arman Oruc, a Goodwin attorney.

Even so, Oruc said, the administration is accomplishing something to the extent it opens a productive dialogue on how the country thinks about anti-competitiveness.

"They're asking, is [the current way we look at antitrust] the right prism through which to look at these laws?" he said.