When Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg announced in May he would allow company employees to work remotely after the pandemic ends, he was just one of many business leaders to give the go-ahead to a permanently distributed workforce.

But he also caused a stir when he filled in details of his plan; it entailed adjusting pay based on location. A software engineer who moved to Reno to take advantage of the nearby mountains, for example, would earn less than those at the Menlo Park headquarters.

"If you live in a location where the cost of living is dramatically lower, or the cost of labor is lower, then salaries do tend to be somewhat lower in those places," Zuckerberg said.

But not everyone thinks setting pay by location is a good idea.

"Cost of living adjustments are ... a deeply unfair and bad practice," Salesforce product management director Blair Reeves said. "People doing the same jobs and providing the same value should be paid the same."

For CFOs of companies planning to allow a distributed workforce post-pandemic, how the debate over pay unfolds can be informative.

Pandemic disruption

About 42% of U.S. employees are working remotely, estimates show, and a significant portion of them — two-thirds in one survey — would prefer to stay remote after the pandemic ends.

Some 80% of CFOs surveyed by Gartner in April said they planned to let some employees remain remote post-pandemic, although the average percentage of permanently remote employees would be relatively small, about 5%.

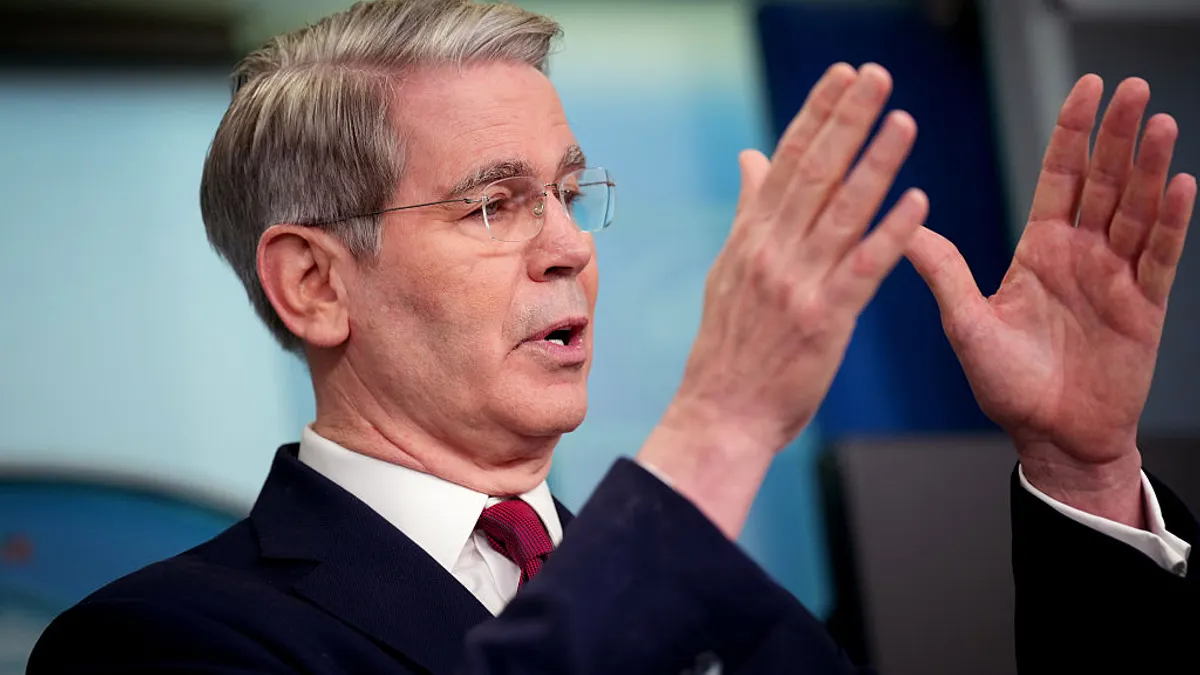

"Most CFOs recognize technology and society have evolved to make remote work more viable for a wider variety of positions," Gartner research vice president Alexander Bant said.

In the same survey, 13% of CFOs said their companies had already started reducing its real estate footprints.

Dell Technologies plans to cut its real estate footprint by about 40% over the next three years, mainly through attrition as leases expire, CFO Tom Sweet said on an MIT Sloan virtual CFO summit panel in early December.

"We have sales and other offices that, when you look at utilization rates, it's time to do something different," he said.

Paycheck arbitrage

For employees, the chance to move to a more affordable area, without changing jobs, promises ample benefits, including improved quality of life.

"It's no surprise many are considering relocating — particularly workers living in congested and high cost of living cities like San Francisco and New York," says Glassdoor Chief Economist Andrew Chamberlain.

For a software engineer living in a high-cost city, the chance to move to a lower-cost area can mean a big bump in retained income, what is sometimes called paycheck arbitrage — the same concept that leads companies to move operations to lower-cost areas overseas. In this case, though, the arbitrage advantage goes to employees.

"It makes no sense paying Bay Area rent if we can earn our salary living elsewhere," one startup employee told Bloomberg News after hearing of Facebook's plan.

Which is why the plan faces pushback; by rearranging the arbitrage advantage from the employee to the employer, it reduces the attraction of remote work and even opens the door to distrust.

"There will be severe ramifications for people who are not honest about moving to a lower-cost area and not disclosing that," Zuckerberg said in his announcement.

Katie Paul, who wrote about the Facebook announcement for Reuters, said the way the company plans to go about it "dashes hopes of paycheck arbitrage" for employees.

Although Facebook pays well — its median salary is $240,000 — the cost of living in Menlo Park is sky high, with a median $2.4 million home price, according to Zillow data in a Marketwatch report.

"[Zuckerberg] dashed a Silicon Valley dream," she says, "that tech workers would be able to take their generous salaries with them as they flee the Bay Area's crushing housing costs, dirty sidewalks and crowded roadways."

Subjective thinking

Reeves said tying salary to location raises issues companies should avoid.

"If someone in San Francisco wants to spend a large chunk of their income on living there, then that's their choice," he said. "But if a remote employee in San Francisco does the same work as their colleague in Little Rock, one person's choice shouldn't be rewarded while the other is penalized."

Surveys taken earlier this year show employees would trade lower pay to work remotely in a less expensive or more desirable area. In one survey, 38% of Facebook workers say they would take a pay cut to work in a different area, and in a survey conducted separate from the company, 32% said they would trade salary for a cheaper location.

Since the start of the pandemic, many CFOs have been surveying their employees to gauge their appetite to return to the office or stay remote.

When payments fintech Square surveyed its 5,000 employees, 15% wanted to remain remote, 15% wanted to return to the office, and the rest wanted a hybrid arrangement that allowed them to do both.

Amrita Ahuja, Square's CFO, says the company is tailoring its plans to accommodate that range of responses. It intends to retain its existing real estate footprint but will reconfigure space to make it more adaptive.

"We probably won't have dedicated desks, but hotelling desks," she said. "and areas for people to get together."

Ahuja didn't address the pay question, but the playbook she described — adjusting plans to meet what their employees want — sounds like a way for CFOs to start a discussion on pay within their company.