The rise of remote workers has complicated what was already a complicated job of collecting state sales tax since the landmark Supreme Court Wayfair decision in 2018, a tax collection specialist says.

The Wayfair decision requires businesses to collect sales tax even if they don’t have a physical presence in the state because of what’s called economic nexus — a designation based on the volume, or value, of sales that businesses conduct in a state.

Each state calculates economic nexus differently, but many follow the lead of South Dakota, which filed, and won, the lawsuit against online furniture retailer Wayfair. It requires a business to collect sales tax if it conducts 200 transactions or $100,000 worth of business in the state in a year.

Other states might require both a volume and a value threshold to be reached. New York, for example, requires both $500,000 in value and 100 transactions before economic nexus is established.

Further complicating the calculation is the type of service or product the company is offering. Although states generally charge sales tax on products, not all charge tax for software products or services.

California, for example, charges no sales tax for software, whether it's offered as a product or a service. But in many states, software products and services are taxable — 12.4% in Tennessee, for example, and 7.4% in Texas.

Remote employees

Since the pandemic, the complexity of calculating a company’s state-by-state tax collection obligation is increased further as employees work remotely. It only takes one employee living in a state to establish physical nexus, triggering a sales tax collection obligation there.

“This has hiring implications,” Michelle Valentine, CFO and co-founder of Anrok, a tax compliance software company, said in an Airbase webcast. “Finance leaders don’t want to get in the way of hiring [and retention] goals, [but you must] be compliant in any jurisdiction” employees are in.

Remote employees can change physical nexus considerably. Traditionally, physical nexus applied only to states a company had a store, office or warehouse in. Depending on where remote employees live, the number of states that create a physical nexus obligation can jump considerably.

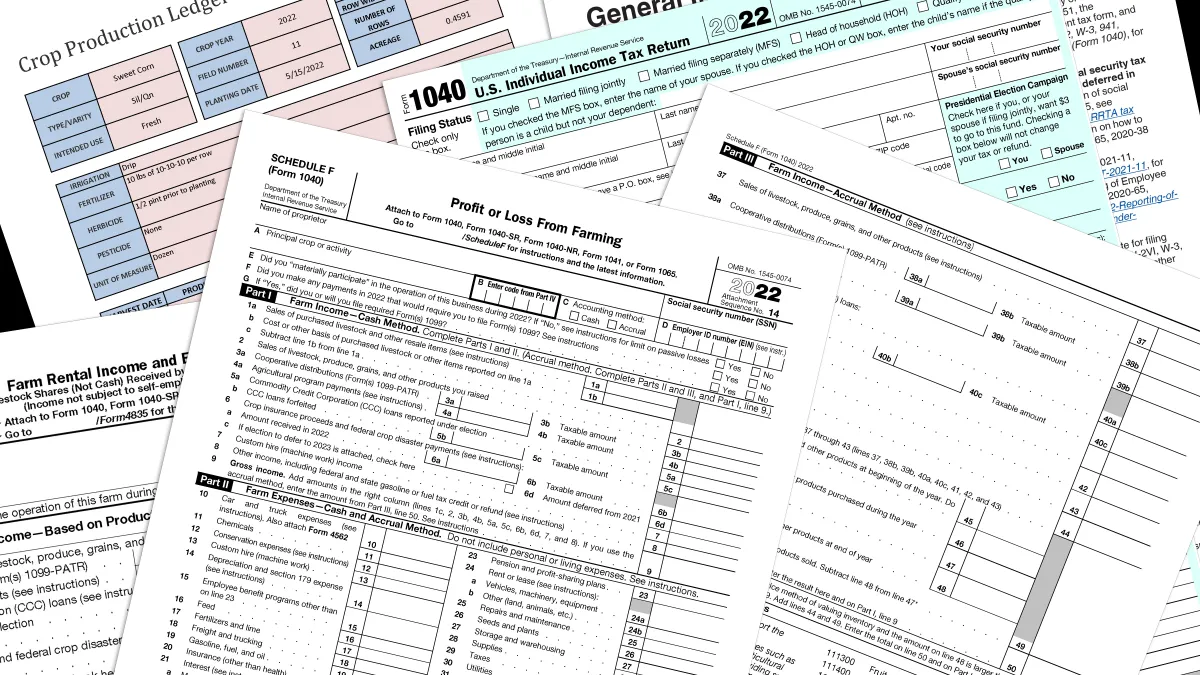

Adding up the types of nexus, both economic and physical, each with its own rate and taxable products and services, creates a complicated obligation to not only track but systematically collect and remit taxes in each state.

“This means for you as a finance leader you not only have to think about physical presence, when it comes to sales tax, but you also have to track your economic presence across states,” Valentine said.

Past obligations

For finance leaders just now focusing on how their organization’s obligations might have expanded because of remote workers, the first task is deciding what to do about past obligations that haven’t been accounted for.

If a company’s past obligations are small — maybe just a few dozen transactions or a few thousand dollars in value — it might ignore them and just focus on its going-forward tax obligations, but that decision comes with obvious compliance risks if it turns out they met the threshold for nexus.

“If you don’t have too much historical liability, [we have seen some companies] just decide to comply prospectively,” Valentine said.

Consequences differ by state, but generally there are penalties and interest-rate charges on past-due obligations.

Based on a calculation her company conducted that factors in average penalties and interest-rate fees and a state’s share of U.S. GDP, companies face an average 4.3% weighted non-compliance obligation.

“So, not charging sales tax can result in roughly a 4% drag on profitability and material cash outflows on achieving sales tax compliance,” she said. “That’s a direct impact to your bottom line.”

For companies wanting to settle past non-compliance, they can do so the first time they register their tax liability in the state and add the past-due amount, plus penalties and interest-rate charges, with their first remittance.

An option she’s seen taken up by bigger companies or those with large past-due remittances is submission of a voluntary disclosure agreement (VDA), effectively a request for a break on penalties. These companies work with one of the Big-Four accounting firms or another third-party consultant to prepare the submission.

“You come forward to your state and say, ‘I’ve actually been in your state for some time,’” she said. “‘Can you forgive some of my past penalties and reduce the interest rate and I’ll pay the sales tax amount? I’m in the process of getting compliant going forward.’ That tends to take a few months, and there is a cost to doing that, because you do need an outside accountant. But if you’re a large company, that process might be worth it.”