When Pete Mariani joined Axogen in early 2016 as its CFO, the company's products were making a difference in the lives of people with nerve damage, but it was under-capitalized and lacked a sizable investor base. The reason was bad timing. Back in 2007, just as it was considering going public to capitalize on the release of its first product, an advanced nerve graft that could help people regain functionality and feeling to an injured area, the recession hit.

“They got the company launched in 2007 and hit all the milestones the venture capitalists wanted them to hit,” Mariani told CFO Dive. “In normal times, the company would have done a huge IPO — $50 million, $60 million, maybe $100 million — and advanced the commercialization of the product but the company ran right into a recession, and there was no money.”

The company promoted its chief commercial officer, Karen Zadedrej, to CEO, and she nurtured Axogen through the recession.

“She took the company from about 40 employees to about 12, preserved our clinical programs, preserved a sales force of three, and basically went door-to-door to keep the company afloat,” Mariani said.

Reverse merger

The company’s fortunes started turning in 2011 when it completed a reverse merger with LecTec, the maker of Icy Hot patches that had lost much of its product market share to companies that had exploited its patents to make knock-offs.

By 2010, LecTec was no longer a viable operating company but was sitting on about $12 million from patent-infringement settlement awards.

“It became a shell company with cash,” said Mariani, who started as a public auditor with Ernst & Young in the late 1980s. “You can make the analogy that the reverse merger is a lot like a [special purpose acquisition company], but the genesis of those two versions is different. Normally you form a SPAC and go raise money for the purpose of finding a company to invest in, but LecTec had actually been an operating company.”

The merger was completed in 2011, making Axogen a publicly listed company on Nasdaq and paving the way for a few small capital raises.

Investor outreach

When he was introduced to the company, Mariani said, he found an operation with great potential but inadequate commercial presence and without the investor base that typically supports a growing medtech company.

His charge, he said, was helping create an investor outreach program to get the company in front of the typical medtech investor.

“We were able to do that and made a couple of other, smaller equity raises,” he said. “So, from about 2016 on is when we started to grow the commercial side of the business, and we’ve been growing quickly with a much better capitalization structure since then.”

Nerve repair

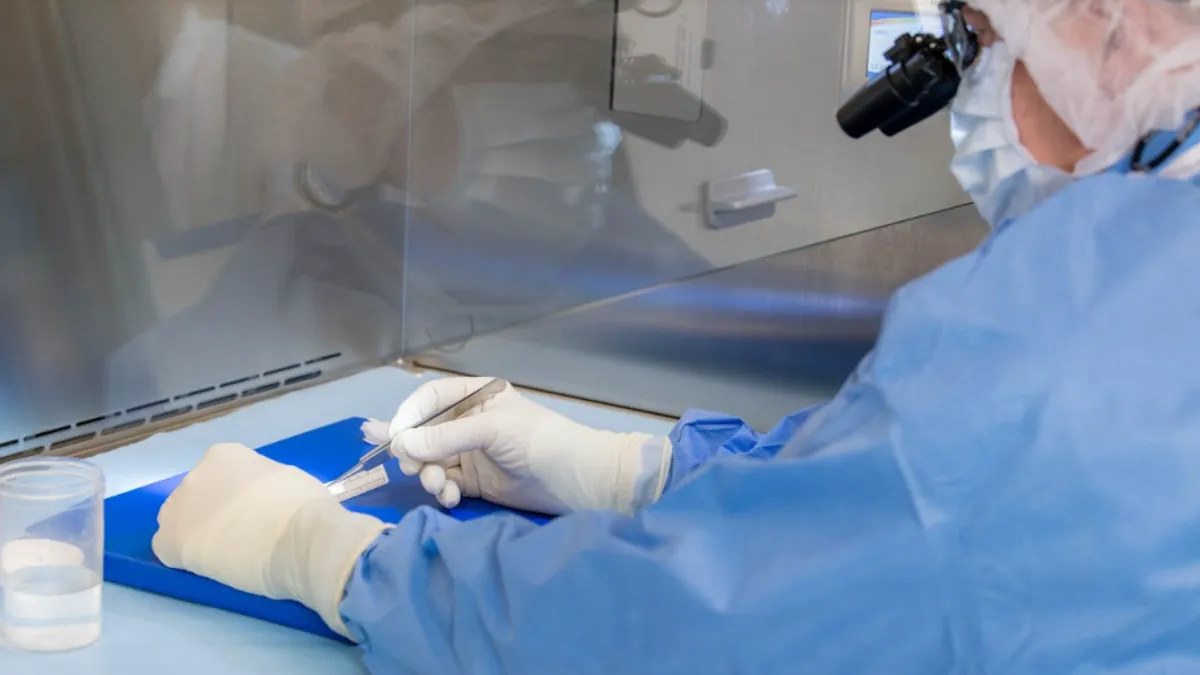

Axogen’s four commercial products help surgeons prevent the loss of, or restore, functionality and feeling in patients who’ve suffered nerve damage. Its advanced nerve graft uses donated tissue to repair damaged nerves, typically for patients who’ve been involved in a trauma.

Its newer products tackle nerve issues using what Mariani calls tubes and caps. A pair of tube products lets surgeons tie damaged nerve ends together until they heal, and a cap product it introduced just as the pandemic hit helps surgeons prevent phantom limb syndrome in amputees, among other clinical applications.

“There’s nothing phantom about it,” he said. “It’s very real. If you’ve amputated the leg below the knee, that nerve that used to go to your foot is still active and it’s telling your brain that my foot hurts and it's because that nerve didn’t come to an end correctly. So, with the nerve cap, you can wrap the end of the nerve and the nerve fibers will grow into the cap a little bit, run out of nutrients and come to a calm end.”

Zone of profitability

Despite the pandemic, the company grew 5% last year, fueled by an 18% surge in sales in the second half of the year. It's currently generating about $100 million in annual revenue with 80% margins.

“We’re in what I refer to as the zone of profitability,” he said. “We’re close to break-even on a cash flow basis and if we wanted to be at break-even and get to profitability quickly we could. But we have the liquidity on the balance sheet that will allow us to continue to make investments that we want to make to continue to drive top-line growth. We’re making these investments with an eye towards profitability because we don’t want to get too far away from the discipline we have in place.”

The company invests about 18% of cash in R&D and clinical trials. As a medtech company, its products are regulated under the Food and Drug Administration’s 510(k) compliance process.

“Our tissue-based product is approved under the tissue regs and we’re in the process of converting that over to a biological product,” he said. “We’re well on the path to do that.”

The surgeon-conversion cycle, as Mariani calls it, is relatively slow because of the nature of nerve damage. In a typical scenario, surgeons will try one of the company’s products in a group of patients and then wait a year to monitor their progress. Only after they’re comfortable they've achieved the results they wanted do they commit to using their products as part of their standard procedures.

“Nerves regenerate at about the same rate that your hair grows, so about a millimeter a day,” he said. “If you have an injury to your hand, it might take six to nine months to get a full recovery, so a surgeon can’t come out of the surgery and know exactly that they got a good repair.”

The company’s getting to the point where there’s a substantial amount of clinical reports backing the efficacy of its products, but it remains a slow conversion process, he said.

“There are enough surgeons who know enough about it that the conversion cycle might speed up a bit,” he said, “but for now we have a slow conversion cycle of surgeons. You really only have one shot to get a nerve repair done right; if you do it and it doesn’t heal, you really don’t get a chance to come back and fix it.”

The company was able to fix it’s funding problems, though, and now it’s on a firm growth footing, Mariani believes, with more products in the works.

“We’re a biotech company,” he said. “We’re going to live and die on innovation. So, we have to have an allocation of money in R&D and we expect them to deliver, and we’ve got clinical trials. We’re developing the data that’s going to help drive the top-line revenue growth and we’ve got product development activity that’s going to keep products coming into the business over the long term.”