When cloud-based customer support company Zendesk was preparing to go public in 2014, the investment bankers who were on deck to underwrite the deal recommended it hold off. The stock market was in choppy waters and the share prices of the public companies that Zendesk was using as comparables for valuation purposes were down 20-25%. But Alan Black, Zendesk’s CFO at the time, recommended the company stick with its plan to proceed.

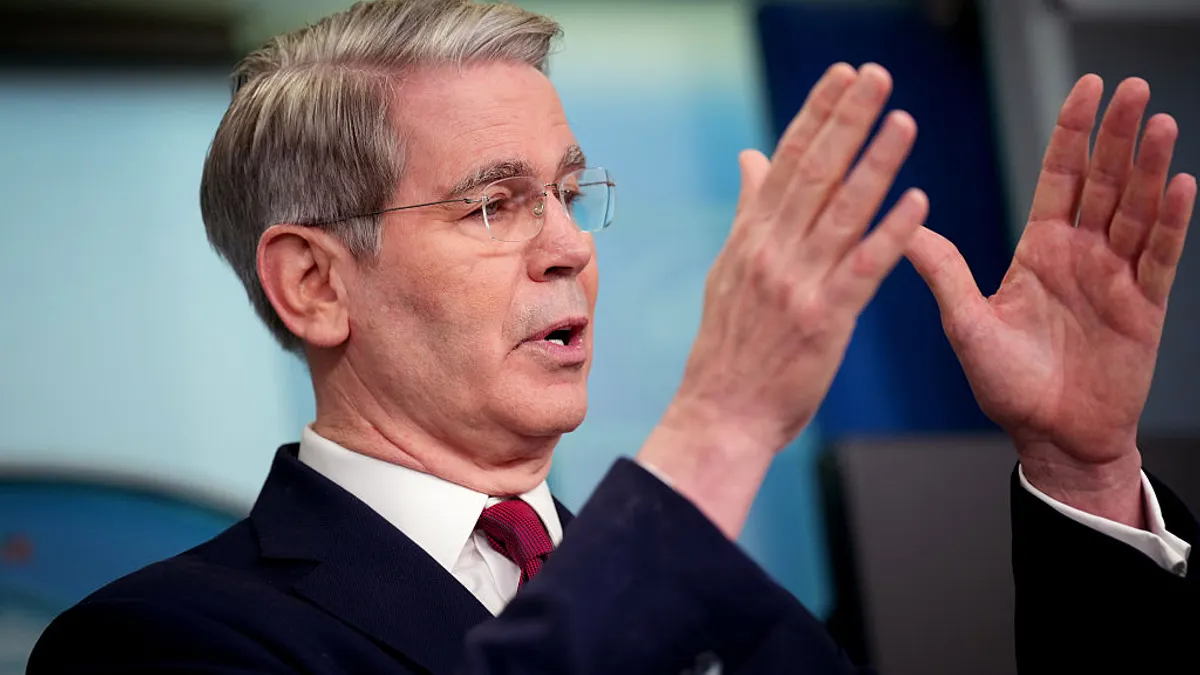

“We got to the end of the third day of our roadshow in New York and it was a sea of red on the Street,” said Black, today founder of Surfspray Capital, a firm that helps technology companies prepare to go public. “We got to the plane to fly the next day to Boston and the lead banker got on and asked me whether I had a Plan B. As you can imagine, those weren’t words I was excited to hear.”

Delaying the IPO seemed like the wrong choice, Black said in a webcast hosted by spend management company Airbase. The company was cash flow positive, and although it was losing money, that was normal for a software-as-a-service (SaaS) startup. In any case, there was little indication the market would be better in six months, he said. If the company held off going public, it would have to tap private equity markets again, something it didn’t want to do.

“We ultimately decided that, if we need capital, let's go for it,” he said.

To help it convince public investors it was well-positioned for its IPO despite the choppy market, Black contacted the venture firms that had already put money into the company and asked them to consider putting forward a show of support in the order book in case it was necessary. The goal was to buoy on-the-fence investors by showing that the company’s backers continued to believe in it and were ready to put more into it.

“All of our VCs put in orders at 30% above the high end of the range,” he said. “We didn’t end up needing it. We had a terrific run from that point onward and [a few days later] the book was fully covered and the following Wednesday we priced the deal and allocated shares.”

Black said the company ended up allocating about 7% of the shares to the venture capital investors “who had come to our rescue,” he said.

On the day of its public offering, the company’s shares soared 44%, sending its market valuation to just under $1 billion, making it one of the period’s big success stories, especially for cloud companies, which at the time were trying to win over skeptics.

Black's lesson from the experience is to go public when the company thinks it’s ready and not based on market timing.

“It’s coming up on eight years later and markets between then and now have been low and they’ve been high,” he said. “It’s usually never as good or as bad as you think it is.”

IPO swim lanes

When he advises companies on their IPOs today, Black says, he takes what he calls a four swim-lane approach.

1. Team strength. The first swim lane is to create the finance and accounting teams that the company will need to get it ready for, and then through, the IPO.

“Say you have somebody in the controller role that has been in a public company before and has been through an IPO,” he said. “That person has a lot of horsepower to be the person in that chair if the company ultimately goes public. If you don’t have a controller, it’s pretty clear you’re going to have to hire someone. It’s about mapping what skills you have across the team at that point in time, then building a roadmap for which ones you need to add.”

The sequence of who to add when is also crucial, because the preparation time for some jobs is longer than for others.

“You wouldn’t hire an investor relations (IR) person to manage communications with investors before you hire someone to manage, say, your stock administration,” he said. “Stock administration is a longer lead-time project that you have to get right before you pull the trigger to hire someone to run IR.”

2. Systems stack. The second is to put in place the operational systems the company will need to scale.

“Nobody would want to go public with Excel as their system of record,” he said. “You can have a company that’s growing 100% year-over-year and has escape velocity in terms of its scale but if the business systems stack isn’t ready, then you’re not going public because you can’t sleep at night.”

3. Investor outreach. The third is getting the company known to investors. Zendesk had some 350 meetings with investors over the years as it was preparing to go public. Another technology company he worked with had close to 1,000 meetings.

Many of those meetings can happen at the conferences that are frequently hosted by investment banks, something that happens more today than in the 1990s, when Black started in the business, he said. At a minimum, the CFO should try to get the company to the point where it’s not meeting investors for the first time during the roadshow, he said.

4. IPO phase. Fourth is project management, which involves going on the roadshow and having the IPO.

Successful debuts

An IPO that leads to a big value pop like Zendesk saw is what makes headlines in the press but in Black's view that isn’t necessarily the mark of a successful debut. More important is how the company performs over the next two years or so. A company that is careful with the narrative it tells investors and then executes consistently well against that narrative is the company that has a successful IPO, he believes.

“It’s always better to focus on where the cap table is two years after the IPO,” he said. “Over that period, your venture investors will distribute and management and employees will get some liquidity. So, if you sell 10% of your company in an IPO, by the time you get two or two and a half years out, 70% or more of the company is owned by institutional investors. You’ve [essentially] had six or seven IPOs in terms of the number of shares that have had to be soaked up by public investors.

"Those companies that excel at both guiding carefully and delivering consistently over and over again against what they said they would do earn the public investor’s trust, so they do absorb those shares," he said. "If the stock is up from the IPO price nicely and you’ve got super high-quality, predominantly long-only investors in your cap table, then that’s when you give yourself a grade of how well of a job you’ve done as a team.”